Opinion: The painful history of ‘blackface’ is still relevant today

Amidst a discussion of Halloween costumes Oct. 23, Megyn Kelly — host of NBC’s “Megyn Kelly Today” — remarked that “blackface,” or applying makeup to make oneself appear black, is “OK” in certain circumstances. This sentiment is not only incredibly racist, but clearly Kelly’s white experience has left her totally clueless as to why.

Kelly’s ignorant comments, similar to the use of blackface, have had far reaching and unintended consequences. One such consequence was the cancellation of “Megyn Kelly Today” and NBC cutting ties with the host.

During the incident, Kelly sat with other news and television personalities and discussed politically correct and offensive Halloween costumes. Kelly was ranting about people classifying certain costumes as offensive — and the discussion took a bad turn when she asked, “What is racist?”

Kelly acknowledged that people consider blackface racist but finished by saying, “That was OK when I was a kid, as long as you were dressing like a character.” Shortly after the offensive comments were released, chaos ensued. Oct. 26, NBC announced that “Megyn Kelly Today” was cancelled.

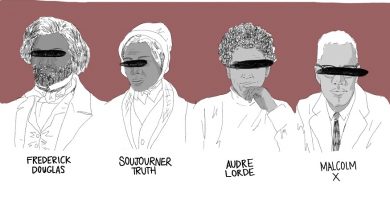

Kelly was confused as to what made blackface on Halloween so racist, clearly indicating that the disgraceful history of blackface was lost to her. For others who are unsure why, here is a brief history lesson:

In the mid-1800s, blackface became a popular form of entertainment that consisted of white actors and comics smearing black ash on their faces to mimic black individuals — hence the term “blackface.” They often wore clown-like makeup to exaggerate facial features. This was popularized by actor Thomas D. Rice’s performance in the caricature act “Jump Jim Crow,” where he sang and danced in blackface.

The point of these performances — known as minstrel shows — was to make a mockery of plantation slaves, which led to the further dehumanization of black people. The caricatures were portrayed as lazy or buffoonish, and at the time these characteristics were attributed to slaves. Images of blackface were commonly used as propaganda against black culture. This was inadvertently done to justify slavery and to disenfranchise and dehumanize an entire race of people.

The use of blackface continued into the 20th century, appearing in popular books, music, TV and the marketing of many commercial items. Famous celebrities such as Shirley Temple, Bing Crosby, Fred Astaire and even Bugs Bunny are culprits of blackface. This reflects the weight that blackface had in American entertainment — the negative narrative that it portrayed of African-Americans was interwoven into the very fabric of society.

At its core, blackface began as a way to further humiliate, degrade and dehumanize African-Americans. It reinforced white supremacy power structures and made it clear that African-Americans were seen as inferior to white individuals.

The wounds caused by this degradation are still fresh and deep. Kelly’s comments reflect a broader, and incorrect, narrative held in America: that we are a “post-racial” society and racism is no longer a problem.

The reality is that communities of color are still impacted by the legacy of racism and the stereotypes that accompany it. Racism may be less overt, but economic, social and political equality are far from realties in America.

Blackface is, to this day, a racist symbol that perpetuates stereotypes and further mocks and degrades African-Americans. Our society should condemn this continued dehumanization and remember that blackface, even used to represent a character, is never OK.