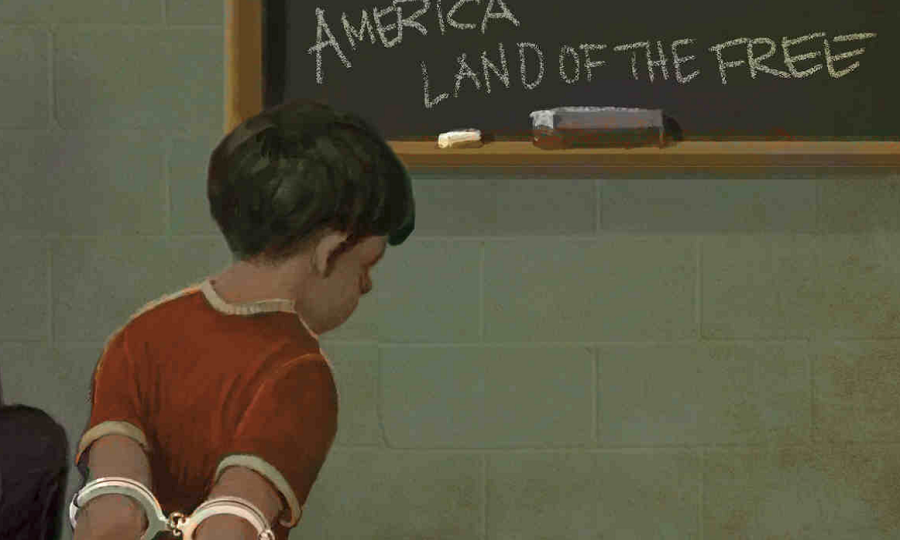

Locking Students Up For Missed Assignments

In 1993, 13-year-old runaway Becca Hedman was murdered. A man had offered her money for sex, but, unsatisfied with the results, hit her on the head six times with a baseball bat.

Heartbroken, her parents encouraged legislators to create a law known as the Becca Bill, which would allow judges to imprison children for noncriminal offenses like running away and skipping school, ostensibly to protect them from ending up on the streets like Becca. Among its provisions is the requirement that when a student has seven unexcused absences in a month, or ten in a year, a teacher must file a petition with the courts.

When it comes to truancy, the bill doesn’t seem to be working. According to a report by the Washington State Center for Court Research, truancy rates have fallen by 0.6% among kindergarteners through eighth graders over the last decade, but risen by 4.8% among high school students. Furthermore, despite the law, teachers only file petitions one-third of the time they are required to. Thanks to this inefficiency, the report was able to analyze the difference between students who did receive petitions and students who did not, and found that they had only a negligible difference in GPA, future excused and unexcused absences, and graduation rate.

Clearly, locking kids up isn’t solving anything. Yet four Washington legislators still think it’s the solution.

House Bill 2513 will encourage courts to order truant students to prove they have completed all of their assignments. One missing assignment, and the student would be found to be in contempt of court and face up to seven days in juvenile detention, or a fine of up to two thousand dollars per day.

Does anybody really turn in every single one of their assignments? I’ve never managed to pull this off, and I graduated from high school with a GPA of 3.9. You don’t have to do everything perfectly to succeed in school, you just have to show that you understand the material. And that’s how it should be.

Chronically absent students sometimes have good reasons for missing school. Some do it to avoid bullying. Others do it out of fear for their safety: a study by the University of California, Davis, showed that in high-poverty areas, students who felt very safe at school were 44% less likely to be truant than those who did not. Still others have to work or care for family members, and school conflicts with those obligations.

Students with significant impediments to their ability to succeed in school shouldn’t be held to a higher standard than their classmates. That’s unrealistic and cruel.

Despite concern for the students’ future, detention often does long-lasting damage. Detention has been found to cause depression and suicidal ideation, with some researchers estimating the suicide rate in juvenile detention centers to be two to four times the national average. Incarcerated students also are less likely to return to school afterwards: The Department of Education found that less than 15% of incarcerated ninth graders finished their education.

Despite its purported intentions, detention also may encourage students to commit crimes. In San Francisco, students placed in the community-based Detention Diversion Advocacy Program had only half the recidivism rate of those in detention. Similarly, Texas researchers found that students in community-based treatments were 14% less likely to commit future crimes than students who were imprisoned.

One Oregon study suggested that these effects are the result of bringing delinquent students together: youth treated in group environments were more likely to engage in substance abuse and violence than those treated individually. In a crowded detention center, even students who have done nothing but skipped a worksheet may be negatively influenced by their peers.

“Locking up kids is the easiest way,” says San Jose Police Chief Bill Landsdowne. “But once they get in the juvenile justice system, it’s very hard for them to get out.”

Schools are meant to teach students skills they need to succeed as adults, a process which can indeed be impeded when students miss assignments. But by holding struggling youth to a standard considered unrealistic for most, HB 2513 permanently damages their chances of success even further. In order to ensure the best future for all students, this bill must be defeated.

Please visit: app.leg.wa.gov/pbc to encourage legislators to vote “no” on HB 2513.