Writers’ Guild of America strikes for the first time since 2008

Changes in the media landscape have made it difficult for the average writer to make a living wage.

Many people outside of the film and television industries imagine anyone who works in Hollywood to be wealthy and lead a glamorous life. But the current writers’ strike is shedding light on the many who are struggling to make ends meet.

“Working as a staff writer, I was still broke, still on Medicaid,” writer for FX’s hit “The Bear” Alex O’Keefe tweeted last month, “The studio wouldn’t fly me out to the writers room in LA, so I worked from my Brooklyn apartment. My heat was out that pandemic winter, my space heater blew out the lights. I worked on episode 8 from a library.”

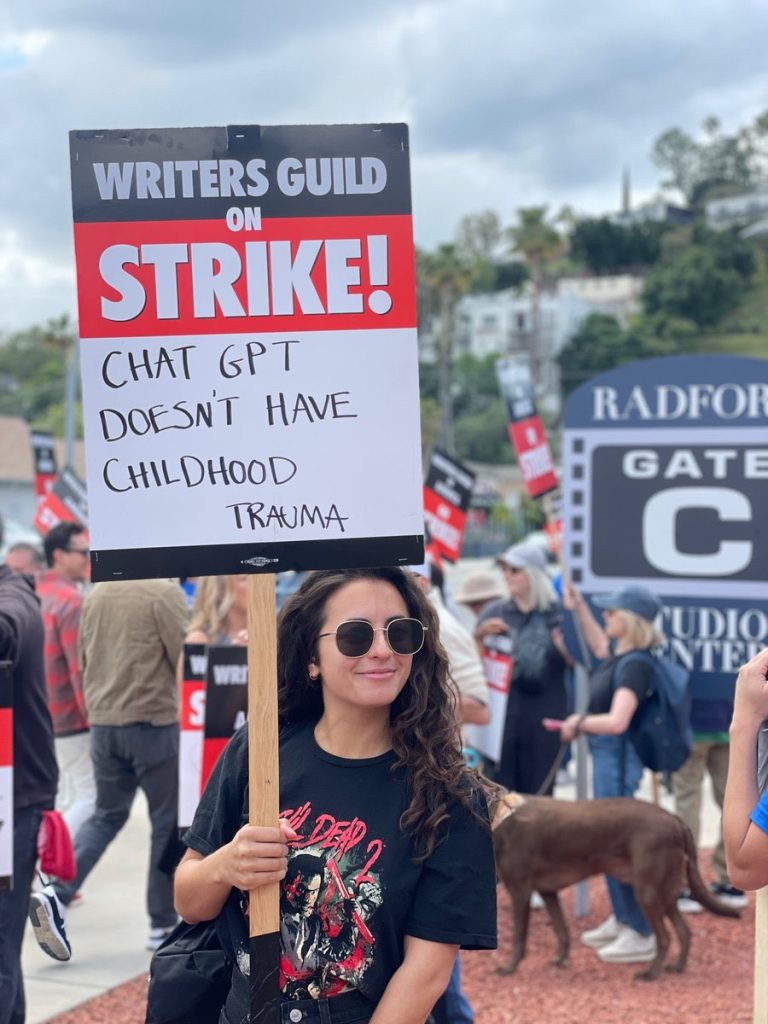

Sadly, O’Keefe’s story isn’t rare. The situation is so dire that at the beginning of this month, the Writers’ Guild of America (WGA) authorized a strike after six weeks of attempted negotiations with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP), who represent the major Hollywood studios. Over 10,000 television and film writers who belong to the union are refusing to work until their demands are met. Reactions have ranged from supportive, to confused, to hostile.

During the last WGA strike in 2007-2008, one of the main issues writers fought for was fair compensation for online distribution. However, because this was before now-giants like Netflix and Amazon began producing content, the gains of that strike were mostly related to purchased downloads (such as through the iTunes store) and ad-supported streaming.

Today, with the ubiquity of streaming services, production studios now have a completely different model of turning a profit. Rather than primarily making money from movie tickets, DVD sales, digital downloads and ad revenue from television and the internet, studios now heavily rely on customers paying subscription fees for each streaming service. Writers today don’t get much of a cut from this revenue stream (if any), no matter how popular the show or film ends up, because studios have refused to include updated compensation models in new contracts.

This shift in monetization has also caused studios to change their strategies in how they produce and release media. New films are made available on streaming services much more quickly relative to physical releases, in order to incentivize subscriptions. Some have argued that this leads to a decrease in ticket sales, a form of revenue which writers are more likely to get a cut of than subscription fees.

Scripted television season orders have been reduced, in most cases, from the former standard of twenty or more, to a meager six to ten episodes. This has led to much smaller writers’ rooms–referred to as mini-rooms–with shorter durations, meaning fewer writers are being paid and given less time to create our current favorite shows.

All of these changes, compounded by the looming threat of advancing AI, have created a landscape in which it is increasingly difficult to make a living as a writer. For every well-known, well-paid, continuously employed Hollywood writer, there are hundreds more struggling to make a decent living.

“The great news is that, thanks only to our union, we have incredible health insurance. If you make a little over $40,000 a year in writers’ guild money, you will get access to that healthcare,” said writer Sasha Stewart in a recent TikTok, “The problem though, is that writers now are having longer gaps in employment. They are having a harder time because the rooms are so small, and for such a short period of time.”

“This is what the writers’ strike is fighting for,” Franchesca Ramsey, a writer, actor and producer, explained in a video to her followers, “fixed residual income based on streaming viewership, and restrictions on mini-rooms so that you aren’t overworked and you aren’t underpaid.”

Some have voiced online that they cannot sympathize with these writers while other professions, such as teachers and healthcare workers, continue to go underpaid.

“We are not in competition with each other,” Ramsey pointed out to one such detractor, “We’re all being taken advantage of by corporations and the monster of capitalism.”

Even within the film and television industry, there are many other workers who are arguably underpaid and deserve fairer compensation. Though some are upset by the strike disrupting their own ability to work and get paid, others recognize the importance of this fight, and have joined the strike in solidarity.

The strike has led to a hiatus on productions such as The Tonight Show and The Daily Show. Other shows and films currently being shot have shut down in solidarity with the strike, or have been forced to shut down by striking writers and their supporters. This is being done in order to draw attention to the importance of having writers present during the entirety of production, not just in the writers’ room. The longer the strike continues, the more of an impact these shutdowns will have on future releases.

The Writers’ Guild of America summed up this battle in a statement to Insider: “When the studios invest millions into producing a certain film or series, they can find it in their budgets to pay us for the value we create.”

For many of us in this age, films and television are the main way we consume art. That’s why the few at the top of the industry make millions–because so many of us value what is being created. But these productions require the work of hundreds, sometimes thousands of people to reach the standards we have come to expect. All of these people, including the writers, deserve a higher return on the value they had a hand in creating, not just the executives who have the final say.