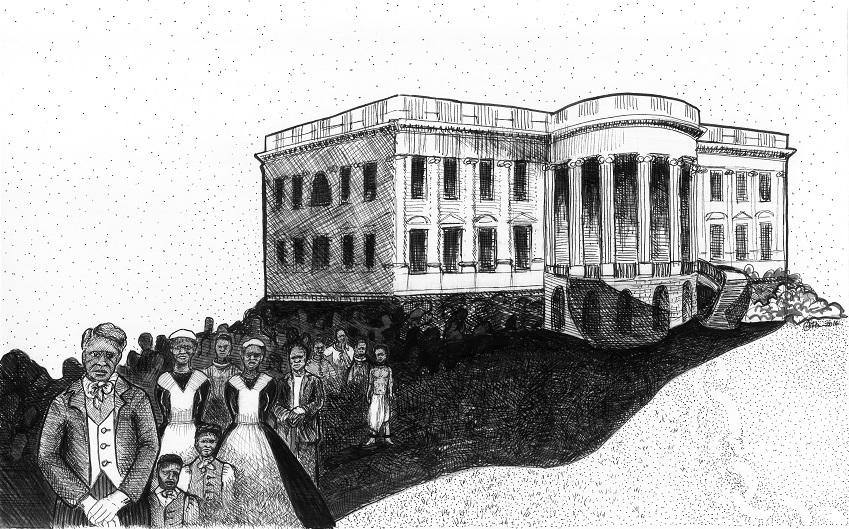

The Invisibles Brings Slavery in the White House to Light

Barack Obama and the first family may be seen as the first African American family in the White House, but that’s simply not true, and it was this idea that sparked Jesse J. Holland. His book, The Invisibles: The Untold Story of African American Slaves in the White House, is Holland’s attempt to bring recognition to all those people—slaves—who came before.

With all but two pre-Civil War presidents being slave owners, Holland has a lot of history to sift through, starting with our first president. Holland spends most his time on the first five slave-owning presidents—out of the first fifteen presidents, only John Adams and John Quincy Adams did not own slaves—with nearly fifty pages devoted to George Washington’s slaves. Ironically, Washington never lived in the White House; the book’s title would be more accurate if it was the untold story of slaves and the presidency. Still, the stories of Washington’s slaves are among the best-documented, historically, and they’re well worth reading: from William Lee, Washington’s devoted personal slave, who rode with him into battle and was even featured in portraits with him, to Hercules and Oney Judge, who were among only a few people to ever escape from being enslaved by a president.

One of the most fascinating things about the book is how the slaves interacted with their presidential masters. While many, if not most, longed for their freedom, there were some who valued their service over their freedom. For example, Elias Polk, a slave of our eleventh president, James Polk, refused to claim his freedom while in a Free State, stating that he’d “sooner die than run off.” Even after the Emancipation Proclamation, he served Sarah Polk, President Polk’s widow, until

Holland gets into more than just slavery as related to the presidents and the White House; he also delves into a brief history of slavery in the United States and laws regarding slavery. These parts can feel like padding, as it’s not “on topic.” It can be educational—did you know that at one time, if a woman married a slave, she’d be enslaved too?— but it feels as if the author is trying to hit a certain page count. At 225 pages, it’s already a shorter book, and without these chapters, it would not be manuscript length. True, Holland says in the foreword that this is only a “first look” at slavery in the White House, but at the same time, it feels it should be longer and more on-topic.

This is a problem that pops up periodically throughout; Holland can get so absorbed in one topic, like Andrew Jackson’s horse racing, that it takes away from the stories of the slaves themselves. Some background is relevant, but Holland can get consumed in the interesting little bits of history to the point of distraction. Holland is occasionally confusing, mainly when trying to explain slave genealogy, but for the most part, he is a clear and entertaining writer.

Overall, The Invisibles: The Untold Story of African American Slaves in the White House is well worth a read, especially if you’re a history buff or want to pick up something for Black History Month. Even if you’re just intrigued by the topic, you’ll find it worthwhile. Just don’t be surprised if you end up wanting more.

ANNA K. FERN