WA history museum’s new exhibit explores Indigenous past, present and future

“This Is Native Land” is the newest permanent exhibition at the Washington History Museum, opening back in October.

By Michaela Ely

The newest permanent exhibition at the Washington History Museum, “This Is Native Land,” explores our state’s history through the lens of Native experiences and voices.

This exhibit was co-curated by UWT professor and member of the Puyallup Tribe of Indians, Dr. Danica Sterud Miller, and Todd Clark, a member of the Wailaki tribe in Northern California. Clark is also the founder and curator of IMDMN, a nonprofit organization that advocates for contemporary native art and artists.

The exhibition includes a variety of mediums by Native artists through which to explore and understand the space. There are videos throughout the exhibition and interactive elements.

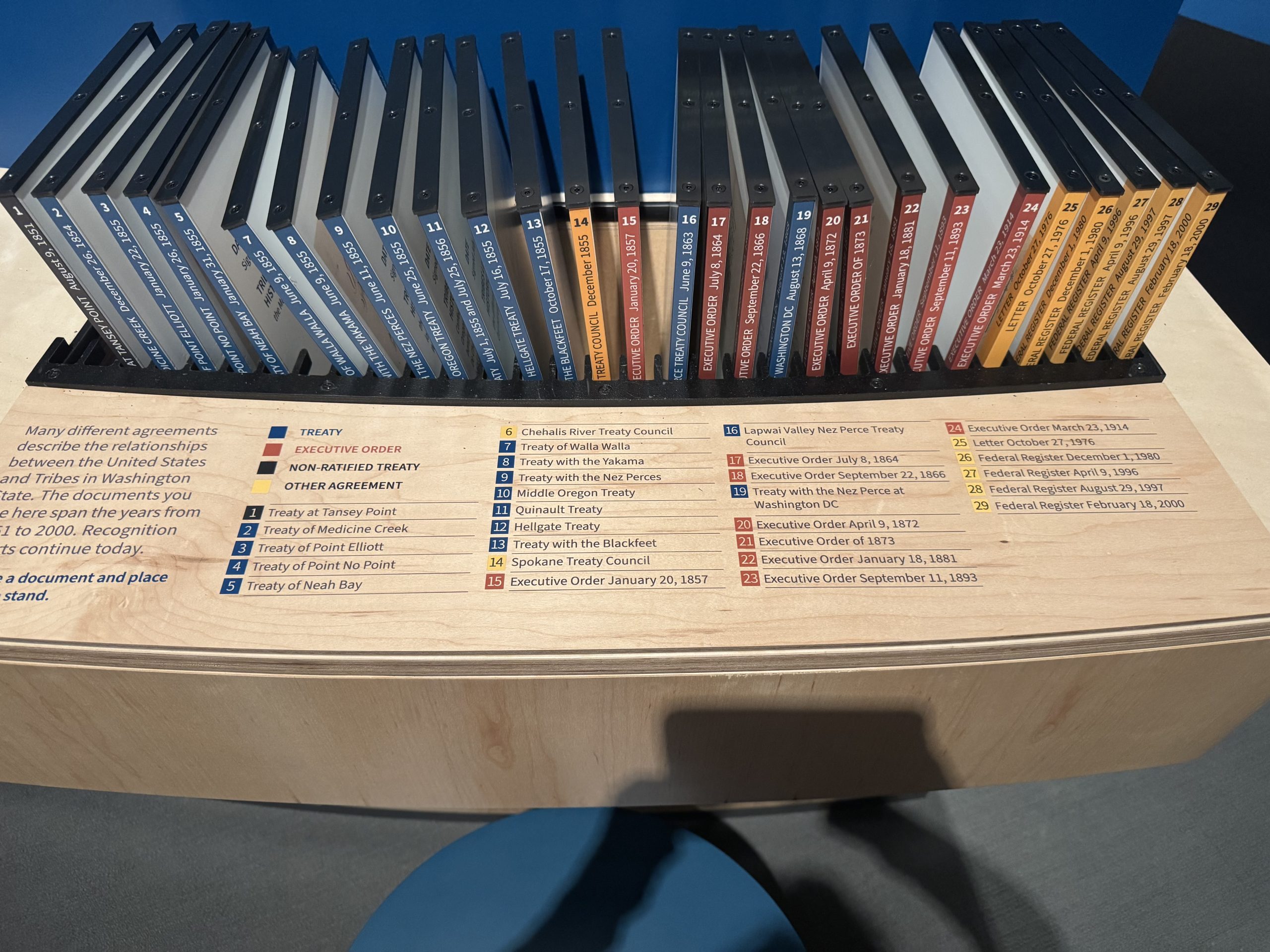

Something that stood out to me in particular was that the treaties for tribes in WA were all printed on these wood blocks that you could take out and read.

“One of the things that I’m really proud of, because I’m a nerdy academic, is the treaty part, how all the treaties are there,” said Dr. Sterud Miller. “One of the things that I learned as a professor is that a lot of my native students hadn’t read their treaties, and they didn’t really know where to access them. And they are accessible on the internet, for sure, but here they’re tangible.”

Treaties are considered to be the supreme law of the land via Article VI of the U.S. Constitution. They are meant to uphold important rights for Native American tribes such as fishing, hunting and gathering.

These rights have come under scrutiny, resulting with the Fish Wars in the 1960s and 1970s. The Fish Wars were a series of protests by Native American tribes in the Pacific Northwest to advocate for their fishing rights promised by the Treaty of Medicine Creek.

This exhibit also explores concepts such as indigenous sovereignty and resilience, informed by challenges of boarding schools, removal from land and forced assimilation. In 1886, the federal government began dividing Puyallup reservation land into what was called an allotment. These allotments were meant to assimilate Native people and families by forcing them to adopt the mindset of the settlers when it came to agriculture and land ownership. These allotments set up a framework to follow in 1887 when the General Allotment Act, also known as the Dawes Act, was passed.

This exhibition also delves into the rights given to tribes who are federally recognized. Federal recognition allows tribes to be accepted and recognized as a sovereign nation in the eyes of the federal government.

29 tribes in the state of Washington are federally recognized. However, there are over 300 tribal entities in the state as many tribes were forced to combine due to treaties and executive orders. Of the tribes left in Washington state, nine are still not federally recognized, including the Duwamish tribe whose historical homelands exist in modern day Seattle.

One of the more interesting parts of this exhibit is that the content is meant to evolve and change over time.

“We created a model that can bring in more stories. There’s nothing about that exhibit that is static,” said Dr. Sterud Miller. “My hope is that other institutions will follow a native led model, right? Because this is native led, by myself and Todd Clark, and that other institutions will understand the importance of letting natives tell the story.”

Part of the exhibition highlights the current and historical practice of Tribal Canoe Journeys. Originally, canoe journeys were ways to travel to large, intertribal gatherings, providing the opportunity to share stories and build relationships. However, by the late 1800s, large tribal gatherings had been banned.

The first modern example of this practice occurred in 1989 with the “Paddle to Seattle” as part of Washington state’s centennial celebration. Since then, Tribal Canoe Journeys have been hosted annually by a different tribal community along the Northwest coast.

“This Is Native Land” provides a new lens through which to understand the history of our state, the good and the bad. It is an exceptional example of what happens when you promote native voices, rather than ignoring or silencing them.