UW study reveals how teen brains aged during the pandemic

The University of Washington Seattle released the results of a study on teenage brains during the pandemic on Sept. 9, 2024.

By Michaela Ely

A study conducted by the Institute of Learning and Brain Sciences at the University of Washington revealed that the pandemic aged the brains of both male and female teenagers, with the girls experiencing the brunt of the impact.

The study was longitudinal and collected data from participants ages nine to 17. The researchers conducted MRIs of the participants in 2018 and 2021 to measure any differences that would have been acquired as each participant either approached, began or experienced adolescence.

The results determined that teenagers experienced premature brain maturation over the course of the pandemic, with girls experiencing an average of 4.2 years and boys experiencing an average of 1.4 years, according to the study.

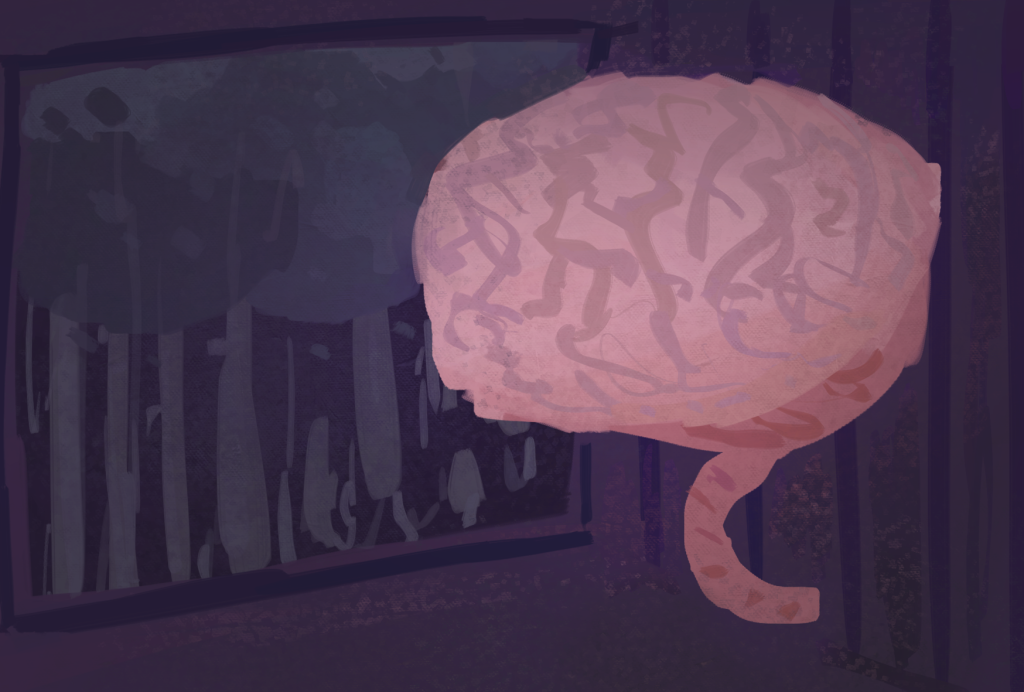

This maturation was measured by the thickness of the cerebral cortex, the outermost layer of brain tissue. While this tissue naturally thins with age, it can be accelerated by chronic stress. A thinner cerebral cortex at a younger age is often associated with an increased risk in developing anxiety or depression, according to the study.

“[I have seen] an increase in social anxiety, depression, substance use, self-harm or death, delay in emotional development, and school or work struggles. All around, [the pandemic] impacted the youth in a way that will change our culture moving forward with physical and mental health,” Licensed Clinical Therapist and Founder of Karis Collective Charissa Walson said.

The study originally began in 2018 with the goal of measuring changes in brain structure during adolescence. However, when the pandemic hit, the original intent of the study was no longer feasible, which shifted the goal. Research Scientist Neva Corrigan, the lead author of the study, decided to use the data to make estimations about the impacts of the pandemic on the brain.

“Once the pandemic was underway, we started to think about which brain measures would allow us to estimate what the pandemic lockdown had done to the brain. What did it mean for our teens to be at home rather than in their social groups — not at school, not playing sports, not hanging out,” Corrigan said to UW News.?

Using the data from 2018, the researchers designed a model that measured expected thinning of the cerebral cortex during adolescence. The brains were then reexamined in 2021 with about 80 percent of the original participants returning. The reexamination showed an accelerated thinning of the cerebral cortex that was more pronounced in females. This is believed to be due to the differences in necessity for social interaction.

A study done by the Institute for Biomedical Sciences of Georgia State University found that females value same-sex interaction as well as being more sensitive to oxytocin which is released from the reward center of the brain. The study goes on to explain that the rewarding properties of social interaction are more present and more impactful in females.

“I think that [the pandemic] definitely made me very anxious about social interaction because I wasn’t around people for a long time, so it was hard for me to transition back. And then I also felt depressed because I missed social interaction a lot so even though I was taking classes online I was pretty unhappy because I wasn’t able to meet new people or create bonds during that time,” UWT alumni Isabella Pettis-Infante said.

The cerebral cortex can begin thinning as early as 4.1 years old and naturally thins with age. It was also found that significant events in life, particularly stressful ones, cause the cortex to thin more rapidly. However, a separate study conducted by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America did not find any statistically significant gender differences.

“The pandemic made a pretty big impact on me, I mostly can say in school I didn’t really get to socialize with my peers the way I used to, and I am a very big hands-on learner with teachers,” Mikalah Davis told the Ledger.

Davis was a student during the pandemic in the Puyallup School District at the age of 15 when the social distancing mandates hit Washington state. For 18 months, Davis could only interact with her peers virtually or six feet apart under the mandates.

The thinning of the cerebral cortex is likely irreversible, but the researchers believe it is possible that the thinning may slow over time with normal social interaction. There is also potential for continued research as in older populations the thickness of the cerebral cortex is correlated with ways to measure cognitive brain function such as processing speed, according to the researchers of the UW study.

Thinning of the cerebral cortex can also be linked to higher rates of depression and stages of mental diseases like Dementia and Parkinson’s, according to the Journal of Alzheimer’s disease and the Journal of Neurology, Neuropsychology and Psychiatry.