Why We Need More “White Privilege”

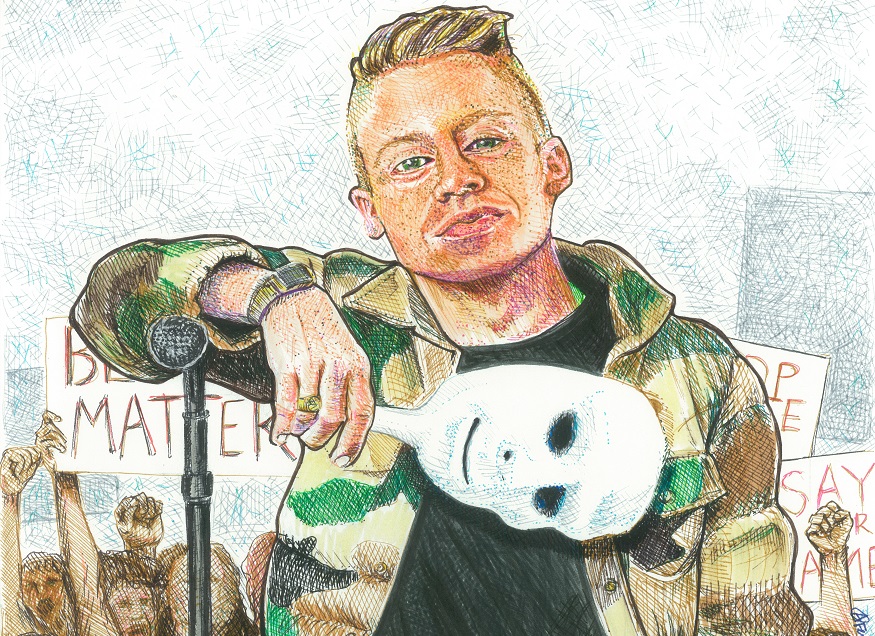

When Apple Music suggested I listen to Macklemore’s new song, I expected something fun and upbeat. While I knew he wouldn’t be rapping about money, sex, or drug use, I figured he’d be celebrating something usually looked down on by the hip-hop community—whether it was wearing used clothing, driving old cars and mopeds, or being gay.

What I did not expect was a confused and introspective song about race and culture. As soon as the tone of the song became apparent, I tuned out my husband’s talking (much to his annoyance) and listened to the lyrics.

“White Privilege II” is a song about confusion. As a rap artist, Macklemore connects with the black community and their current struggle for social justice. However, as a white man he feels like an outsider—a man who never has, and never will, deal with the consequences of actually being black. When he calls out Elvis Presley, Miley Cyrus, and Iggy Azalea, he is not pointing a finger at who to blame, but telling himself that he is no different than them: born with white privilege but benefiting from black culture.

At the end of the nearly 9-minute song, I paused, thought for a second, and declared, “I love it.”

Did I love it because I, as a woman of mixed race, feel culturally conflicted? No. Did I love it because I am deeply involved in racial issues? Again, no.

I loved it because it does what too many songs fail to do.

It said something important.

Culture influences music and music influences culture. This is inarguably true. But this two-way street is not even. Music has a stronger influence on culture simply because it has a much larger reach than any one cultural trend. If the residents of a trendy neighborhood suddenly start wearing clothes from the Goodwill, it is unlikely that the rest of the country will follow suit unless a #1 song about thrift-shopping hits the airwaves.

But this megaphone possessed by the music industry has generally not been put to good use. The standard song—be it pop, country, hip-hop, or rock—talks about relationships, money, partying, and other fairly non-controversial topics. This is likely due to the pressure put on artists from music executives trying to sell as many albums as possible by offending the least amount of people as possible. This unwanted pressure is apparent in songs like “Love Song” by Sara Bareilles, in which she responds to execs requesting a love song, and the lesser known “Y’all Want a Single” by Korn, in which they blast executives for forcing the band to create manufactured, cookie-cutter songs and then blaming them when they turn out to be unpopular.

While there are some artists that are purposefully shocking precisely because they want to stir up controversy and sell more albums (think Marilyn Manson), it is generally the other way around. A glance at the top 10 songs in the nation right now is a testament to the music industry’s mantra of “tread lightly.” Songs by Justin Bieber, Adele, the Chainsmokers, Selena Gomez, and Rihanna are about relationships. There’s a song about childhood nostalgia by Twenty One Pilots, yet another party song by Flo Rida, and a song by Alessia Cara about not wanting to be at a party. Partying and relationships are the music industry’s bread and butter.

When an artist does decide to express an unconventional emotion however, it often turns out quite well. Think of Alanis Morissette’s angry ballad “You Oughta Know,” where she throws out the traditionally feminine ideals of unaffected poise and grace and instead embraces her resentment and bitterness. Think of Kanye West’s unassailable narcissism, which has kept his album sales consistently high despite President Obama calling him a “jackass.” Think of the Dixie Chicks’ response to the public backlash they received after coming out against George W. Bush—“Not Ready to Make Nice” won three Grammy awards. And Rage Against the Machine, the permanently angry and unapologetically political rock group has sold over 16 million records worldwide.

People respond well to those they deem sincere. (One great example of this is the popularity of Donald Trump.) When people sense they are hearing truth, they gravitate towards it. But with truth comes controversy, which is something most music executives are loathe to court. Nevertheless, recording artists have an obligation to elevate the issues they care about, simply because they have the ability to do so.

When celebrities get involved in social issues, the entire country takes notice. Oprah Winfrey, who started out as a talk-show host, was placed on TIME magazine’s list of the most influential people on 10 separate occasions. Bono was named Political Journal’s most politically effective celebrity of all time for his humanitarian work. Even Pamela Anderson, best known for her blonde hair and her big—you know—was awarded the Linda McCartney Memorial Award for her animal rights activism.

Macklemore long ago realized the power he possesses through sheer influence. “White Privilege II” is a personal reflection, a cultural critique, and a call to action. It is a matter of opinion whether one agrees with his message or not. But, to quote Spiderman’s Uncle Ben, “With great power comes great responsibility.” When you have the power to send a message, send a message that matters.