Genetic Mapping: How Much Do You Really Want to Know?

It was spring break and I was looking for something to watch on Netflix, and being the true geek that I am, I was perusing the documentaries. Suddenly, an episode of NOVA caught my eye. The title was, “Cracking Your Genetic Code.” Remembering that I had a genetics class this quarter, I decided it was a good fit.

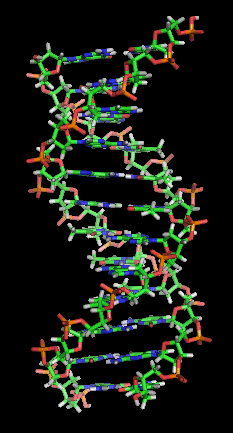

In the year 2000, after 13 long laborious years, the entire 6,000,000,000 letter human genome was finally completely mapped. It was a monumental occasion, and it changed life as we know it… forever.

In May 2013, the media was swarming as actress Angelina Jolie announced that she had decided to have a double-mastectomy as a preventative measure to avoid breast cancer. She had paid a company to map her entire genome, after which she discovered she was predisposed to breast cancer. She said her reason for going public was to be a source of strength and encouragement to other women. Recently, in March of this year, she underwent another surgery. This time it was a hysterectomy, again citing that she had learned she had the genetic mutation now known to put one at risk for ovarian cancer.

It used to take years and cost in the six-figures to get this done, and was far out of reach for most of us common folk. Now, there are several companies that offer a partial mapping, testing only for certain diseases and conditions, for as low as $99. Results are available in about 45 days, a big reduction from prior technology that had been available.

This opened a whole new can of worms. However, questions were raised as to how easily one’s privacy could be invaded while conducting this “mapping.” What if the information was to become public and people began to be turned away from jobs or refused medical insurances based on the results? “We are now in an unprecedented era,” said Catherine Elton, one mother interviewed on the NOVA program, “If I had known prior to birthing my son, that he would have cystic fibrosis, would I have taken the risk, and if not, look what I would have missed” referring to her 5-year old son.

Francis Collins, head of the Institute of Health, decided to explore this idea of genetic mapping. He sent his sample to three different companies. What did he learn? All three companies listed him as high risk for type two diabetes. However, all three had different ideas about his risk for prostate cancer. One of the companies listed him as high risk, another listed him as average, and the other, low risk.

“Learning about the type two diabetes changed my life.” said Collins, “I lost 27 pounds last year, and I am eating healthier.”

But what about diseases like Parkinson’s or ALS, or Alzheimer’s? Do we want to know if we are predisposed to these, currently incurable diseases, or would that be too big a burden to bear, skewing our outlook on life, and perhaps, robbing us of what joy might be available to us?

Oddly, as I arrived in my “Genetics and Societies” class one morning, our professor, Dr. Jack Vincent, announced we would be starting our quarter by viewing a movie. Gattaca, a movie made in 1997, explored some of the possibilities and dangers, of genetic mapping. In this film, set in the “not so distant” future, children were no longer conceived naturally, but pieced together and engineered genetically to supposed perfection. Those who chose to have “faith” births, gave birth to invalids or degenerates. The movie mainly centers around two children, one valid, and one invalid. The genetically engineered child, a predisposed athlete, who had failed to win first place, was in an “accident” leaving him paralyzed. Meanwhile, the invalid, with big dreams of working on Titan (one of the 14 moons of Saturn) but who was not engineered for perfect health, plots to “purchase” the genetic ID of the now crippled super-human. Using this man’s ID, despite having a bad heart that would otherwise lock him out of the program, this “invalid” beats all odds to pursue his dreams. I don’t want to tell too much of the story, in case you care to view it yourself.

But the movie raised a lot of questions to be pondered. Do we want to know we have been born with a heart disease that will likely kill us by the time we are 30? Do our parents want to know this? If someone steals your genetic identity, how would you get that back? Are there moral implications involved? Is it ethical? There are no black and white answers to these questions seeing as for most people, it boils down to personal beliefs.

I realize that I have painted a sinister picture of genetic mapping and have certainly written this in a way that would predispose a reader to be alarmed. And yet, in the right hands, genetic mapping has done remarkable things. Cancer Institute of America, and other “cutting-edge” medical facilities, have used genetic mapping to tailor cancer treatment in unique and personalized ways, learning from the genome which medication will have the best results on a given patient. They have saved countless lives with this information. I can’t help but be happy for these people, and must consider this too, before I weigh in.

In the end, I am surely more comfortable using the genome mapping for finding cures and preventive medicine than I am using it to specifically engineer babies to have pre-existent destinies, based on a “skills lot” given to them prior to birth.

It seems we are back to the same moral and ethical dilemmas that come with all technological and scientific advancement. We have to weigh out the long-term effects, study the impact on those whose lives have been altered by the knowledge of their genome, and we have to take it case-by-case. There is not going to be a blanket “all inclusive” answer to these questions considering that how we react and how these matters impact us remain as unique and unpredictable as the human species at large.

You must be logged in to post a comment.