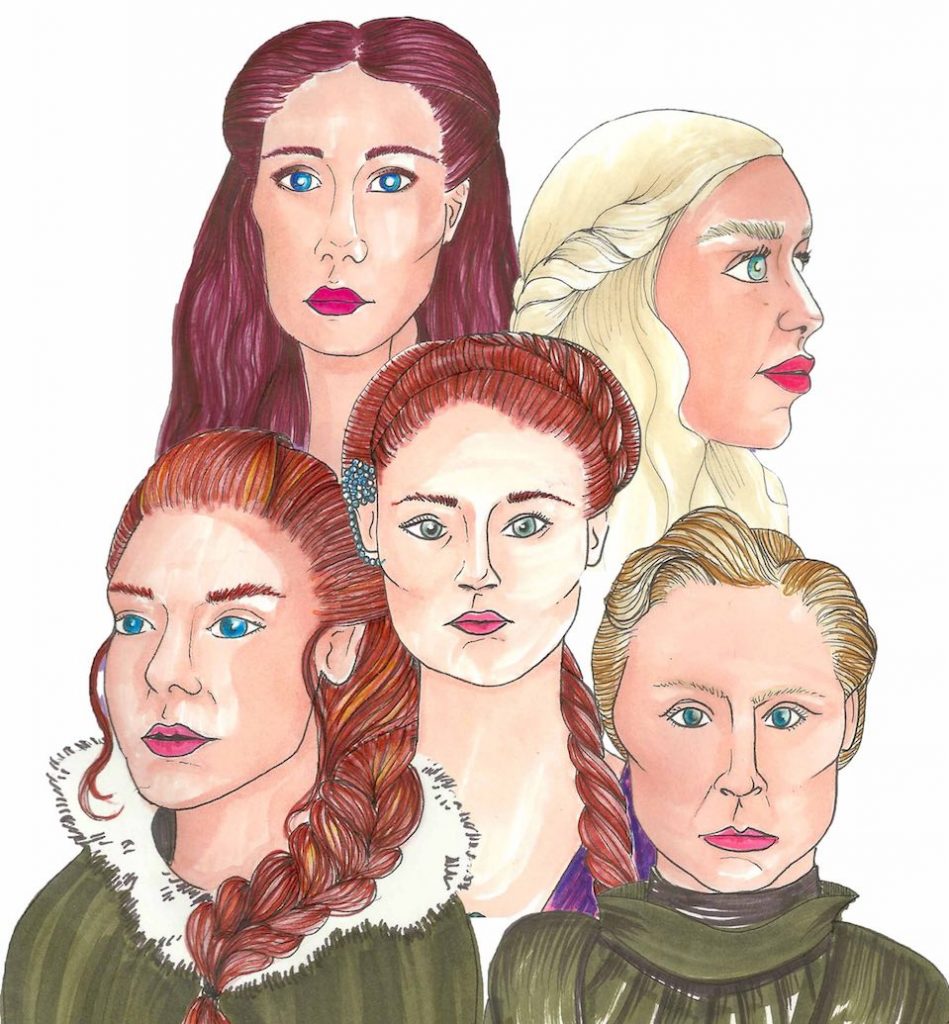

Game of Thrones: Feminist or Femi-not?

The Game of Thrones series is no stranger to controversy, both good and bad. Fans were shocked when the primary protagonist was killed off in the first season. This is good controversy and served to set the show apart as one that does not cater to its fanbase. But the show has also been lambasted for the sexualization and extreme violence inflicted upon its female characters.

In a June 2015 article in Time, journalist Eliana Dockterman argued that the show had been increasing savageries upon its female characters while simultaneously sidelining their storylines. The feminist/pop-culture blog, The Mary Sue, stopped promoting the show back in May of 2015 due to what it viewed as unnecessary rape scenes. And Missouri Senator Claire McCaskill posted on Twitter that she was “done” with the show for the same reasons.

The show is phenomenal in most respects. The production value, score, and costume design alone make it worth viewing. However, given the material the show’s producers have to work with, I am disappointed at some of the creative liberties they decide to take. For example, in the book series, Robb’s wife was not involved in the “Red Wedding”—to avoid having her honor besmirched by Walder Frey, Robb leaves her at Riverrun. Her storyline eventually peters out so it makes sense for the producers to kill her off in one fell swoop. But why they also decided that she and her fetus needed to be brutally stabbed is beyond me. Despite the producers’ sadist tendencies, the world that George R.R. Martin has created in his books has some of the best female characters I have ever come across. Here are some of my favorite female characters and the reasons I love them:

YGRITTE

Yes, Ygritte was wild (can a “wildling” be anything else?), mouthy, and had a healthy dose of disregard for authority. But what I liked most about her was her sexual aggression and cocky confidence. Many strong female characters seem wholly disinterested in men until their equally strong male counterpart breaks down their icy exterior. Ygritte never had this pretension. It was Jon’s walls she had to tear down and she did it with a distinctly male approach: persistence.

Ygritte simply assumed from the very beginning that Jon stole her to be his wife, and, since he succeeded, she had every claim to his body. Despite his resistance in the beginning, Ygritte’s tantalizing closeness and confident swagger eventually broke him down—a tale commonly told the other way around. Never once did Martin present Ygritte as promiscuous, cheap, or easy, as sexually aggressive women often are. She simply knew what she wanted and she made sure that she got it.

MELISANDRE OF ASSHAI

Melisandre is not a nice person. A religious fanatic who is cruel and manipulative, the scope of her influence is terrifying. The show’s producers would have you think Melisandre uses her sexuality to influence men. It is implied that the sex scene between her and Stannis allows her to birth the murderous shadow that kills Renly Baratheon.

In the books, she is much more mysterious. She has somehow gotten under Stannis’s skin, and it is very unlikely that it was through sexual means, as Stannis is known throughout the realm for his stony demeanor and lack of sexual interest. He has fathered no known bastards and is stubbornly faithful to his wife, despite his disinterest even in her. It is Melisandre’s persuasiveness and religious zealotry that makes her a cult-like leader. The queen, Celise, never hints at jealousy, as she sees Melissandre as a priestess, not a mistress. In too many stories, power through manipulation is reserved for the male characters while power through sex is reserved for the female. Martin turned this on its head.

BRIENNE OF TARTH

One may be wondering why Arya Stark didn’t make my list. Arya Stark is brave and ferocious, yes, but, all too often, “strong female characters” are presented as “women who act like men.” Arya Stark is basically a little girl who acts like a boy. There is absolutely nothing wrong with this, but I’ve seen it done to death. Brienne of Tarth is different. She is very masculine, yes. But she is also madly, desperately, in love with Renly Baratheon. Martin could have made her asexual (never mentioning her sexuality) or a lesbian. But no, he made the tomboy of all tomboys blush with feminine modesty at the slightest glance from the man she loved.

Yes, Arya is a little girl and therefore too young to show an interest in boys yet. But I get the feeling that an Arya-romance storyline would be all too cliche; there would be some boy that she’s best friends with until one day sexual tension crops up out of nowhere. Commence awkward pubescent romantic feelings. But I love that Brienne’s character never went that route. Brienne, knowing she surely had no shot of her love being requited, instead vowed to defend the life of the man she loved. As a member of the Kingsguard, she is required to never marry or have children. Sacrifice of this measure is a common trope for female characters, but Martin wrapped it in the most unusual of packages.

DAENERYS TARGARYEN

This is a given. She went from a scared little girl to a confident queen. But how she underwent this transformation is what’s important. In a typical story, the female character would use her wits and bravery to escape the man that she was sold to. She would go from victim to survivor. Instead, Daenerys does something I didn’t expect—she decides that she isn’t a victim.

Many people were uncomfortable with the sex scene between the Khaleesi and her Khal in the first season. Daenerys is supposed to be a young girl, thirteen to be exact. Khal Drogo, on the other hand, is clearly a grown man. In the book, the marriage consummation is presented a bit differently. Daenerys is still frightened and uncomfortable, but she notes that Drogo has a gentleness to him. She senses that what is happening is not about violence and subjugation, but tradition and duty. (This was not conveyed well in the show.) She sees opportunity in these circumstances. She decides to open up to Khal Drogo and to embrace the power that comes from her position. Daenerys Targaryen, above all, is an opportunist. She does not wait for fortune to favor her. She looks at the cards she’s been dealt, saves the good ones, then eliminates all other players until she holds the winning hand.

SANSA STARK

I am so glad Martin included a character like Sansa Stark. In most of the stories I read or shows/movies I watch, the prissy, hyper-feminine character is not meant to be likable. She is usually vain, shallow, passively cruel, and completely superficial. There is typically an antithesis female character who is practical, caring, and enthusiastic, who serves to emphasize how unlikable the traits of an ultra-feminine woman truly are. But Martin not only made Sansa a main character, he made her a “good guy.”

Sansa is truly a caricature of femininity: she is the darling of Septa Mordane, loves beautiful dresses, gallant knights, and romantic stories. She is courteous and flattering. True, these qualities get her nowhere. She continues going from one unfortunate situation to the next. But Martin makes it clear that she is a kind person (a favorite of the caustic Sandor Clegane) whose naivete gets her in trouble, not her femininity. While she doesn’t pull a Daenerys and capitalize on her very useful marriage to a Lannister, she does soldier on bravely, learning how the world works as she goes.

So, which is it? Is Game of Thrones a champion for women or yet another exploiter of them? Let me put it this way: If Tyrion Lannister represents women (ignore the connotations of this and stay with me) the book series is Oberyn Martell and the show is Sir Gregor Clegane. For my diehard fans, this analogy needs no further explanation. For everyone else, let’s just say the show takes the radical and inspired source material and crushes its skull until the soul leaks out.