Racial education is incomplete in many U.S. schools

Every February, U.S. schools focus on racial education, but is it good enough?

This February will mark the 52nd national observance of Black History Month. In a time where Black Lives Matter activists and Critical Race Theory are as commonplace in the headlines as they are around the dinner table, it is especially important that we consider the month of February, and what it means for our nation, for African Americans, and for ourselves.

My experience with Black History Month was personified by casual awareness for much of my life. I grew up in Gig Harbor, a predominantly white community. To count all the Black classmates I had who stuck around for my full K-12 experience, I wouldn’t even need a full hand. I would just need one finger.

Every February, we had a Black History Month assembly, and we did reports on Martin Luther King and the Civil Rights era. We were taught about slavery, segregation and racism, and how important it was that those things never happened again.

However, throughout it all, there was a prevailing undertone that racism and hate were in the past. That all of it happened ages ago, and all of America’s past evils were solved and put into a neat little box which was safely buried in the depths of history.

It wasn’t until I was in my late teens, that I started venturing outside of my white bubble and into the real world that I noticed that things were not as neat and tidy as I had been led to believe. Racism was still very much alive and well.

I am sure my story is not an uncommon one. Many communities in America are predominantly white like Gig Harbor. Depending on the state and school district, many white students receive a similar narrative of racial history in America.

In reality, this narrative is as dangerously incomplete as it is intentionally misleading. Organized suppression of African Americans is still a prevailing sentiment in some corners of American society.

These efforts are not as obvious and out in the open as they used to be. Nowadays they hide behind seemingly harmless zoning legislation and curtains of bureaucratic legitimacy. Yet, they can be found for those who are willing to look for them.

In the 1980s, Ronald Reagan’s infamous War on Drugs was one of these curtains of legitimacy. At face value, nothing seemed wrong to the average American. Drug addiction was seen as an immoral crime at the time and many supported a strong crackdown on drug users and distributors.

Yet what was hidden beneath the War on Drugs was a concerted effort to re-enslave Black people and strip them of their right to vote. According to the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 and 1988, even minor possession charges were met with severe prison sentences and felony charges.

Once in prison, the charged were often put to work without pay, also known as slavery. If and when they got out, those with felony charges had lost their right to vote. Numbers found in the book “From the Folks Who Brought You the Weekend” by Priscilla Murolo and A.B. Chitty, put the number of incarcerated Americans in 1980 at 474,368 and by 1990 that number had grown to over one million.

According to the Divided Justice report, African Americans were over three times as likely to be incarcerated during this time. From 1990 to 2005 the Black incarceration rate grew by 27%.

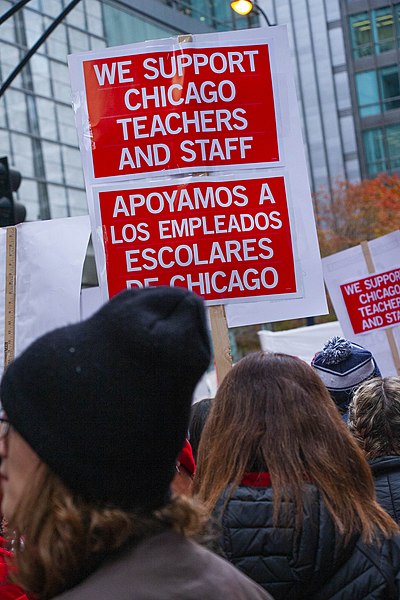

An example of systemic racism can also be found today with the ongoing voting rights debate and the Republican filibuster of the Freedom to Vote Act. According to a report by Public Democracy America, in the wake of Donald Trump’s stolen election lie, 52 different voter suppression initiatives have been passed in many states like Georgia and Texas.

Many prominent politicians, activists and academics across many disciplines believe many of these initiatives are targeted at working class Black people, communities that tend to vote against the Republican Party, according to decades of research conducted by the Pew Research Center.

As federal law supersedes state law, the now dead Freedom to Vote Act would have rendered these racist and undemocratic initiatives unlawful. Yet thanks to the Republican filibuster and the betrayal of Senators Joe Manchin and Kristen Sinema, these initiatives are likely to play crucial roles in future elections.

Unfortunately, race does still play an institutionalized factor in American politics. This is one of the key ideas expressed in Critical Race Theory. Many on the conservative right lambast Critical Race Theory as a hateful lie designed to make white people hate themselves.

I do not think all of them believe this for malicious reasons. The truth espoused in Critical Race Theory is an unpleasant one. People would rather see a pretty lie which tells them their world is just fine, than be faced with something unpleasant which challenges them.

I think this is precisely why my own racial education was so incomplete and why many children in America grow up without a proper understanding of the role race has played and still plays in our society.

I do not think racism is found hidden in every corner of America, and I’ll admit, sometimes I think that political correctness can have an itchy trigger when it comes to broad declarations. I also think America’s history is defined by those who opposed racism, just as much as those who defended it.

It’s a complicated, uncomfortable, and nuanced story. Yet all of it should be taught, not just the easy parts, not just the story of the heroes, but the story of the villains, past and present.

The fact of the matter is that in many schools, this is not happening, kids are being sold a pleasant lie. If we are to overcome racism, I think the first step would be to stop lying about it. Teach Critical Race Theory in schools.