Looking at Macklemore’s “Unruly Mess”

This Unruly Mess I’ve Made is a concept album insofar as the concept is “everything.” In 13 songs it covers topics ranging from a sharply-timed critique of celebrity award shows to overeating and tagging, ending with an extended discussion of white privilege and its relationship to rap and hip-hop. This topical range as well a mix of musical styles makes This Unruly Mess I’ve Made particularly hard to place beyond a few recurring motifs such as weariness and fame (go figure). It’s aptly titled.

This Unruly Mess I’ve Made opens with “Light Tunnels,” wherein Macklemore narrates the night of the 2014 Grammys at which he and Ryan Lewis won for their previous album, The Heist. The track uses hip-hop singer Mike Slap’s melodic vocals, the Seahawks drumline choir, a 12-to-15 piece string section, a harpist, and a dulcimer player to expose his love/hate relationship with his hip-hop career. Macklemore labels the Grammys as a marketing scheme rather than an artistically-motivated event when he raps, “They want the gossip, they want the drama / They want Britney Spears to make out with Madonna / They want Kanye to rant and to go on longer, cause that equates to more dollars.” At the end of the song, orchestral trumpets accompany Macklemore’s nervous-yet-gracious acceptance speech. After his speech, he reveals his guilt over being inescapably trapped as a pop star, saying, “Miserable here but wanna make sure I’m invited next year.”

This sentiment is echoed in “The Train,” a quiet elegy for Macklemore’s family life. The train in question being a metaphor for his music career which he feels “[he’d] be crazy to exit.” He raps about how his touring estranges him from his family to the backdrop of the sounds of a steam train and Carla Morrison’s haunting vocals. Aside from the ethereal noises, her only lines are in Spanish: “Otra cuidad, otra vida,” or, “Another city, another life.” Macklemore further characterizes this sentiment in “Growing Up,” saying, “I’m gonna be there for your first breath / I don’t know if I’ll be there for your first step.”

Both “The Train” and “Bolo Tie” highlight the strains of fame on Macklemore as an individual, whereas “Light Tunnels” and “White Privilege II” examine societal issues through the lens of his personal experience. Doubtlessly the album’s focal single, “White Privilege II” is notable for its thorough examination of white privilege in the music industry in reference to the Black Lives Matter movement (to say nothing of its near nine minute length). “White Privilege II” can only be described as a cacophonous whirlwind of choir singing, sax, and prose—combining a litany of guest speakers including soul singer Jamila Woods into a stirring song.

What carries the song along—and gives it such a fantastic progression—is the minimalistic piano underpinning. Upon the utterance of the line, “If a cop pulls you over it’s your fault if you run,” the piano’s key cover slams shut, cutting the instrument out completely and switching to more emotionally-reflective synthesized tones. This line is spoken by Macklemore imitating an older white mother in a coffee shop. “She” praises him for his positive hip-hop at the same time she generalizes Black hip-hop music as, “…the guns and the drugs / The bitches and the hoes and the gangs and the thugs,” eventually roping the Black Lives Matter movement into the generalization as well. Macklemore has used sarcasm a fair bit in his past work and he uses it quite cuttingly here to caricaturize some of his white fans.

He goes on to connect this perception of himself as the one good (white) rapper to white supremacy, rapping, “And if I’m the hero, you know who gets cast as the villain.” Macklemore clearly feels guilt over being successful more than and instead of many Black artists as a product of white privilege, just like what he expressed about his Grammy win in “Light Tunnels.”

He further declares that, “If I’m only in this for my own self-interest, not the culture that gave me a voice to begin with / Then this isn’t authentic, it is just a gimmick.” He’s talking about cultural appropriation here and how many white musicians have become very successful by capitalizing on Black culture. Importantly, though, the song is addressed not to Black people, but rather to whites. In perhaps the most telling line in the album Macklemore raps, “We take all we want from Black culture, but will we show up for Black lives?” directly addressing his white audience and juxtaposing the cultural boons they have experienced with the ongoing struggle for Black civil rights. That line signals the end of Macklemore’s lyrics in “White Privilege II.” As the piano’s reverberation slowly fades back in several Black speakers come in to deliver lines about Black Lives Matter and how white people can involve themselves. Jamila Woods closes the song out, repeatedly singing the telling line, “Your silence is a luxury, hip-hop is not a luxury.”

Controversial among idiots and merely a dig at Iggy Azalea to surface-level listeners, “White Privilege II” has also garnered some cogent criticisms for its simple hypocrisy. The issue being that Black hip-hop artists have been saying these same things for ages and that Macklemore receiving attention for merely repeating those criticisms as a white musician is a product of the same system he’s denouncing. Macklemore seems to inadvertently address this criticism in “Growing Up” when he advises his children, “Don’t try to change the world, find something that you love … And eventually, the world will change.”

The melodic piano and trumpet-driven song “Need to Know,” featuring Chance the Rapper, criticizes capitalism and society’s obsession with social media, consumer products, and drugs. Then the lyrics turns dark when he raps, “Amen, Satan, told me not to serve, I only think about myself, I only think about my work.” Chance comes in, saying of his daughter, “I’m already afraid of tight clothes / I want all her best friends to be white folks.” He’s alluding to his fear of his daughter being racially and sexually profiled, recognizing that hanging out with white friends would give her some degree of white privilege. Chance admits in a later lyric that “It’s fucked up…” that he should even be thinking of tight clothing and black peers as hazards.

In “Bolo Tie” Macklemore contemplates his fame, rapping, “But where’s the self-esteem when the costume’s removed?” Just like the song “Need to Know,” Macklemore intentionally mimics the generic modern rap and hip-hop sound and lyrics. For example, “Motherfucker, you ain’t my accountant / You don’t know what I’m doing.”

This Unruly Mess I’ve Made touches on a variety of issues when it comes to the hip-hop music industry and society, but Macklemore & Ryan Lewis also threw some party songs into the mix. The first hit of the album, “Downtown,” is an old school hip-hop song about riding mopeds around downtown Seattle. Legendary rappers Melle Mel, Kool Moe Dee, and Grandmaster Kaz bring rowdiness to the song when they rap, “I’m headed downtown, cruising through the alley / Tip-toeing in the street like Dally / Pulled up, moped to the valet.” Operatic singer Eric Nally chimes in, belting, “Have you ever felt the warm embrace / Of a leather seat between your legs?”

The humorous song “Let’s Eat” is relatable to many Americans’ never-ending cycle of wanting a perfect body, but continuing to eat junk food nonetheless. Macklemore raps, “But tomorrow though? I’m a get fit / Get me a fuelband and a fitbit / Get me some workout shoes, and a bench press / Some Lulu Lemons and French press.” But he doesn’t forget about saying a proper goodbye to junk food, adding, “But again, that’s tomorrow / And today man I gotta go big ‘cause it’s my last day / Before I lose that weight, I gotta get one last plate and go big.” The track sample of buying food at the grocery store used in the beginning of the song is a nice touch.

“Growing Up” is a mostly sincere-seeming song composed of Macklemore’s advice to his children on the trite subject of apprehensions about being a father. However, that doesn’t stop Ed Sheeran’s whiny singing of, “I’ll be patient, one more month / You’ll wrap your fingers round my thumb,” from being wholly out-of-place and lacking in subtlety. “Kevin” has a similar tonal problem: It turns out upbeat drumming and choir singing just don’t sync up with angry rapping about a friend’s fatal addiction to prescription drugs.

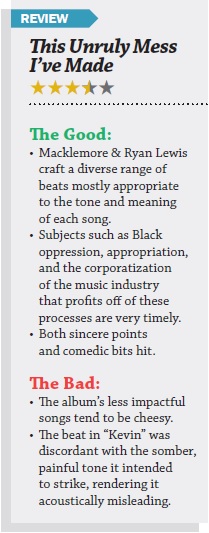

Before, in The Heist, Macklemore was trying to find his place in the hip-hop world as an independent artist. Now, in This Unruly Mess I’ve Made, he’s taking a look back to see not only where he’s come from, but also what the music industry and society have become, expressing his dissatisfaction with them. Despite a couple cringe-y moments, this album is worth listening to not just for its discussion of race issues, but also for the music itself. You might be surprised with the development of the album’s lyrics and beats.

You must be logged in to post a comment.